Organic Chocolate Torte Recipe

Chocolate Ganache Fudge Torte

2 ¼ cups Maple syrup or agave

2 ¼ cups cocoa powder

1 cup coconut oil/butter

1 tsp Red Stuff powder (optional)

1 tsp Green Stuff powder (optional)

Blend maple syrup and cocoa powder in robot coupe.

Add coconut oil and pour into pans immediately

Recipe property of

Marcus Guiliano

Aroma Thyme Bistro

165 Canal St

PO Box 731

Ellenville NY 12428

www.chefonamission.com

2 ¼ cups Maple syrup or agave

2 ¼ cups cocoa powder

1 cup coconut oil/butter

1 tsp Red Stuff powder (optional)

1 tsp Green Stuff powder (optional)

Blend maple syrup and cocoa powder in robot coupe.

Add coconut oil and pour into pans immediately

Recipe property of

Marcus Guiliano

Aroma Thyme Bistro

165 Canal St

PO Box 731

Ellenville NY 12428

www.chefonamission.com

Is that claim on the menu actually true?

By Jan Greenberg

By Jan Greenberg

|

OPPOSITE, CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: 1) Kristin Canty bought a farm to provide reliably sourced ingredients for Woods Hill Table’s menu. 2) Maine scallops, squid ink, angel hair, poached calamari, pickled peppers, fennel and sweet pepper jus at Lautrec. 3) Apple/pork sausage at Woods Hill Table. 4) Lautrec’s chicken and waffles

|

In April, Laura Reiley, the Tampa Bay Times food critic, published a three-part series with the headline, “At Tampa Bay farm-to-table restaurants, you’re being fed fiction.”

Reiley spent months going through the menus from every restaurant she had reviewed since the farm-to-table, sustainable trend began. “Of the 239 restaurants still in business, 54 were making claims about the provenance of their ingredients,” she wrote. “Not all were true.” In one restaurant, the menu contained an opening statement: “This menu is free of hormones, antibiotics, chemical additives, genetic modification and virtually from scratch.” When Reiley asked the bartender whether the cheese curds were indeed housemade, she was told that everything was made in-house from scratch. As it turned out, however, the cheese curds arrived in a box. The fish and chips, cited on the menu as wild Alaskan pollock, was really from frozen Chinese pollock treated with the preservative sodium tripolyphosphate. And the wild Florida gulf shrimp? Farm-raised and imported from India. Reiley is not naive. She has been reviewing restaurants since 1991, including for the San Francisco Chronicle, and wrote that she has always known there are fraudulent menu claims. “Just about everyone tells tales. Sometimes they’re whoppers, sometimes they are the fibs born of negligence or ignorance, and sometimes they are nearly harmless omissions or ‘greenwashing.’” With a circulation of fewer than 500,000, the Tampa Bay Times is not considered a national newspaper. Yet, Reiley’s piece made national news. “I got hundreds of emails, and I talked to people from Michigan, Oregon, Australia, all over,” she says. “This is a huge problem, and people really want to know what we can do.” |

|

true or false?

It’s not a new problem. In the mid-19th century, farmers discovered they could expand their profits by feeding cows the waste from distilleries and producing “swill” milk, to which was added starch, plaster, chalk and eggs to resemble pure milk. In ancient Rome, winemakers sweetened wine with lead, and in the 1700s, when tea suddenly became popular in Great Britain, jail time was imposed on those selling herbs as the real thing. Most recently, in 2013, the international nonprofit conservation group Oceana issued a report detailing the widespread mislabeling of fish, particularly snapper and salmon. Handling and responding to misrepresentation is difficult for producers, who most of the time do not know it is happening, and even when they do know, are reluctant to speak out and jeopardize further sales. Says one farmer who sells livestock to restaurants, “Sometimes what happens is that when a restaurant opens, they have the best of intentions and buy your product. Then, for any one of a number of reasons—perhaps it is it too expensive, too much trouble to make the arrangements to procure, too sea - sonal, whatever—they stop buying, but don’t notice it is still on the menu. Rarely, but sometimes, it appears to be intentional.” Another producer points out that a restaurant will purchase a particular product for a special occasion, such as a wine dinner or farm-to-table event, and then continue to claim that it is using the product. setting the standard

It is a given that running a successful restaurant is no mean feat, and most restaurateurs and chefs want to support local purveyors, serve sustainable ingredients, present an honest menu, and maintain a healthy and economical bottom line. Baldor is a food distribution company that delivers on the East Coast from Maine to Virginia and whose clients range from corner delis to Le Bernardin, Daniel and Jean Georges. From its beginnings as a fruit stand in New York’s Greenwich Village in 1946, Baldor, now based in the South Bronx, sources products from around the globe. |

For the past five years, the company has worked to develop a network of regional producers, partnering with farmers so that restaurants can use the Baldor’s website to order product directly from the farm. Baldor’s buyers work with small producers, visiting facilities and offering trend information and marketing know-how to producers for whom such information is vital but difficult to obtain on their own.

With the click of a mouse, customers can order ducks from Crescent Duck Farm in Aquebogue, New York, turkeys from Northwind Farms in Tivoli, New York, pork from The Piggery in Ithaca, New York, and grass-fed beef from Joyce Farms in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. quality first

Nemacolin Woodlands Resort in Farmington, Pennsylvania, where Kristin Butterworth is chef de cuisine, is named for Chief Nemacolin, a Delaware Indian who, in 1740, blazed a trail through the rugged Laurel Highlands mountains. Pittsburgh industrialist Willard Rockwell established a private game preserve on what is now the resort’s property, and named it Nemacolin. At Lautrec, the resort’s restaurant, Butterworth not only works with the resort’s horticulturists but with approximately 12 local CSAs (community-supported agriculture) and farmers. Although the menu lists the main ingredients of each dish, there are few purveyors named. Local is important, but quality and availability take precedence. “Over the past five years, I have personally forged amazing relationships with farmers and purveyors in the local area, as well as throughout the country,” Butterworth says. “I handle all the ordering for the restaurant and speak with purveyors personally so that we are constantly on the same page. “In my opinion, quality and flavor always trump mass pro - duction. It is my responsibility to our guests to make sure that they get the absolute best product I can source, and that’s my philosophy from the proteins on the plate to the finishing sale.” the farming life

While it’s not possible for most chefs and restaurateurs, sourc-ing from one’s own farm is one way to ensure that what is listed on the menu is what it says it is. In 2013, Kristin Canty, producer of the documentary Farmageddon: The Unseen War on America’s Family Farms, purchased a former supermarket space and opened Woods Hill Table in Concord, Massachusetts. “I asked a farmer friend to help me source for the restaurant,” she says. “He told me there was no way that I would be able to get enough for this many people, and I’d have to purchase my own farm.” |

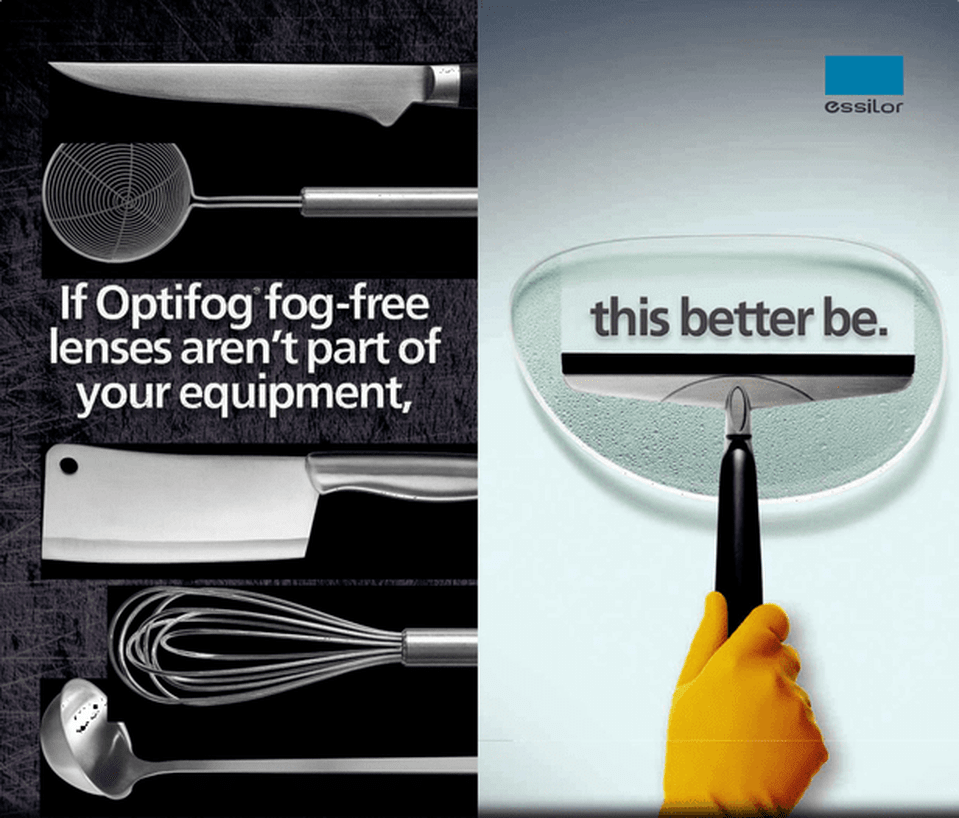

*Each purchase of Optifog lenses comes with four Optifog Activator Cloths, to last approximately one year. Additional cloths may be purchased separately.

©2016 Essilor of America, Inc. All rights reserved. Essilor and Optifog are trademarks of Essilor International. LOPF000138 5/16

©2016 Essilor of America, Inc. All rights reserved. Essilor and Optifog are trademarks of Essilor International. LOPF000138 5/16

|

Canty now raises most of the livestock served at the restaurant on a 265-acre farm. Charlie Foster, executive chef, plans a menu to take advantage of whatever the farm yields each week. “My job is to use the entire animal,” he says. “The idea is to spread out the cost by using the entire animal, so we have a big charcuterie program. We make stocks, and even dog bones, with kidneys and livers from the beef.”

There have been some learning curves along the way. “We again ran out of beef and chicken recently,” says Canty. “We didn’t know the demand would be so great. Luckily, I have a lot of resources, given the documentary I made. So we do supplement with product from other farms, but I go through the Northeast Organic Farming Association, and they have been able to direct me.” chef on a mission Among the most outspoken chefs on the subject of truthful sourcing is Marcus Guiliano, owner of Aroma Thyme Bistro in Ellenville, New York, at the foot of the Catskill Mountains. “When I was just starting out, and going through the ranks, I noticed that chefs were using terms like ‘local,’ ‘sustainable,’ ‘grass-fed,’ but not using the food,” he says. “And it wasn’t just a rarity. One of the chefs was buying tilapia and selling it as red snapper in a $30 entree.” In 2003, Guiliano and his wife moved back to New York to be near family. He opened Aroma Thyme, now certified by the Boston-based Green Restaurant Association and a recipient of CLOCKWISE FROM LEFT: 1) & 2) Charcuterie at Woods Hill Table, left, where most of the livestock served on the menu comes from the 265-acre Farm at Woods Hill. 3) Marcus Guiliano buys meat from a local producer or from a company that has all grass-fed animals raised under strict standards. 4) Woods Hill Table chef Charlie

Foster at Farm at Woods Hill. |

a Wine Spectator award. He also started a website, Chef on a Mission, to detail instances of food fraud and sustainability.

“Now that I have my own restaurant, we can serve food that we believe in,” Guiliano says. “All my ingredients have a purpose, and everything is investigated. I must have some kind of connection with the product along the way.” Although living in upstate New York means he cannot have local products all year, Guiliano is passionate about product quality and production standards. “When I can, I buy meat from a local producer up here where I can see the farm and talk to the farmer,” he says. “But most of the year, I am purchasing from Silver Fern, which has all grass-fed animals raised under strict standards.” Silver Fern Farms is a farmer cooperative representing New Zealand sheep, venison and beef farmers. the right way Basically, it comes down to the chef and owner. “Our philosophy at Lautrec is that every dish should have a story,” says Butterworth. “Traditionally, I will research all product prior to placing it on the menu to ensure that I am properly edu-cated, and I continue that education with the service team.” Chefs must rely on themselves to do the research about what is on their menus, and they understand that customers are in the restaurant to eat, not to be educated. “We don’t want the menu to look like a dictionary,” says Woods Hill Table’s Foster. “It takes away from the enjoyment of what you are eating. “You don’t need to put it out in the open if you are doing it the right way.” Jan Greenberg, author of Hudson Valley Harvest (Countryman Press, 2003), is based in Rhinebeck, New York.

|